Is Manic Depression the Same as Bipolar Disorder? A Comprehensive Guide

Language is the primary tool we use to understand our mental health, but when that language changes, it can leave a trail of confusion. One of the most common questions asked in psychiatric clinics today is: Is manic depression the same as bipolar?

The short answer is yes. However, the transition from one term to the other represents more than just a simple name change; it reflects a massive leap in our medical understanding of how the brain regulates mood. For decades, “manic depression” was the standard label used by doctors and the public alike. Today, “bipolar disorder” has taken its place in the clinical world, yet the old term lingers in pop culture, older literature, and family histories.

This confusion often stems from the fact that while the diagnosis is the same, the difference between bipolar and manic depression lies in the nuance of the definition. In this article, we will unpack the history of these terms, explore the modern reality of living with bipolar disorder, and clarify why the shift in terminology was necessary for better patient care and reduced stigma.

What Is Bipolar Disorder? (Foundational Overview)

Bipolar disorder is a chronic mental health condition characterized by significant, often extreme, fluctuations in mood, energy, and activity levels. These are not the typical “ups and downs” that most people experience in daily life. Instead, they are distinct periods called “mood episodes” that can last for days or weeks.

Mood Episodes Explained

At its core, bipolar disorder involves two emotional poles:

- Mania (or Hypomania): A period of high energy, euphoria, or extreme irritability.

- Depression: A period of deep sadness, hopelessness, and low energy.

Signs of Bipolar Disorder

The signs of bipolar disorder can vary significantly from person to person. While one individual might experience “classic” euphoric mania—feeling like they are on top of the world—another might experience “dysphoric” mania, characterized by agitation and anger.

Common behavioral signs include:

- Cognitive Shifts: Racing thoughts during highs; “brain fog” or slowed thinking during lows.

- Energy Fluctuations: A decreased need for sleep during mania; excessive sleeping (hypersomnia) during depression.

- Behavioral Patterns: Impulsivity and risk-taking (spending sprees, sexual indiscretions) during manic phases.

Gender Differences in Symptoms

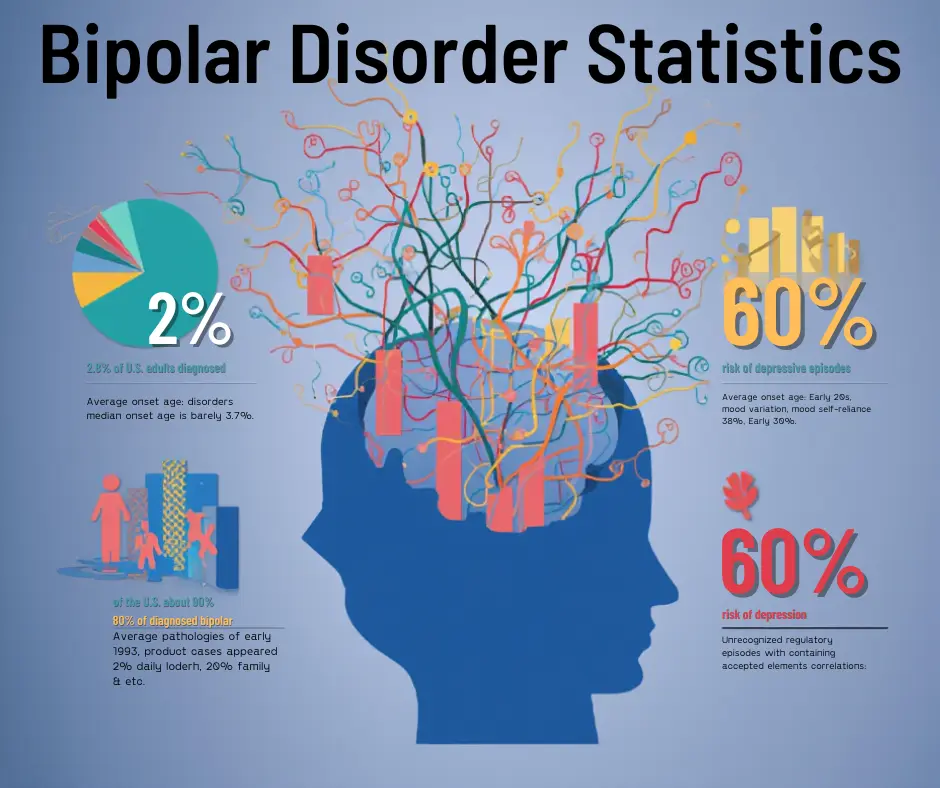

Research indicates that bipolar disorder symptoms in females often manifest differently than in males. Women are more likely to experience “rapid cycling” (having four or more mood episodes in a year) and typically spend more time in the depressive phase. Additionally, women have a higher rate of co-occurring conditions, such as thyroid disease or anxiety disorders, which can complicate the diagnostic process.

What Was Manic Depression? (Historical Context)

The term manic depression (or manic-depressive illness) has roots that stretch back to ancient Greece. Physicians like Aretaeus of Cappadocia first observed that the “fire” of mania and the “darkness” of melancholia were often linked within the same patient.

Origin of the Term

However, the formal medical term “manic-depressive insanity” was coined in the late 19th century by German psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin. Kraepelin was a pioneer who noticed that certain mental illnesses followed a cyclical path of recovery and relapse, rather than a steady decline. He used “manic depression” as a broad category to describe anyone who suffered from recurring mood disturbances.

How It Describes Mood Extremes

In the early 20th century, manic depression symptoms were viewed primarily through the lens of these two extremes. If a patient was seen dancing in the streets one month and unable to leave their bed the next, they were labeled a “manic depressive.” While accurate in describing the “poles,” the term was a “blanket” diagnosis that didn’t account for the various subtypes of the disorder we recognize today.

Is Manic Depression the Same as Bipolar Disorder? (Core Answer)

To be perfectly clear: Manic depression is the same thing as bipolar disorder. There are two different names for the same underlying biological condition.

The Evolution of Diagnosis

The medical community officially moved away from the old terminology in 1980 with the publication of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III). At that point, “manic-depressive illness” was formally renamed bipolar disorder.

Why the Modern Term Is Preferred

Doctors and researchers argue that is bipolar disorder the same as manic depression is a “yes” with a major asterisk. The modern term is considered medically superior for several reasons:

- Scientific Accuracy: “Bipolar” specifically highlights the two “poles” (mania and depression) of the illness.

- Distinction from Unipolar Depression: It helps doctors distinguish between someone who only has depression (unipolar) and someone who has the cycling mood of bipolar disorder.

- Inclusivity of Symptoms: “Manic depression” implies a 50/50 split between mania and depression, but many patients (especially those with Bipolar II) rarely experience full mania, making the old name misleading.

Why Is Bipolar No Longer Called Manic Depression?

The shift was not just about medical accuracy; it was also about the humanity of the patient.

Reduced Stigma

One of the primary reasons why bipolar disorder is bipolar no longer called manic depression is the heavy stigma attached to the word “manic.” In popular culture, “manic” became synonymous with “maniac,” a term used to describe someone who is violent, “crazy,” or dangerous. This linguistic baggage prevented many people from seeking help because they did not want to be labeled as a “maniac.”

DSM Diagnostic Updates

The DSM-III revision sought to create a more clinical, neutral language. By using “bipolar,” the focus shifted from a scary-sounding personality trait to a biological mood state. Furthermore, the rename allowed for the inclusion of hypomania—a less severe form of mania—which “manic depression” failed to describe adequately. This change revolutionized treatment, as it allowed millions of people who didn’t fit the “wild mania” stereotype to finally receive an accurate diagnosis.

Bipolar Disorder: Manic vs. Depressive Episodes

The defining characteristic of bipolar disorder is the transition between two very different states of being. Understanding the bipolar disorder manic vs. depressive dynamic is key to managing the condition.

Manic Episode Symptoms

During a manic episode, a person’s mood is abnormally elevated. Symptoms include:

- Extreme Energy: Feeling “wired” or jumpy, often needing only 2–3 hours of sleep.

- Flight of Ideas: Racing thoughts that move so fast the person may struggle to speak clearly.

- Grandiosity: An inflated sense of self-importance or power.

- Risk-Taking: Excessive spending, reckless driving, or impulsive business decisions.

Depressive Episode Symptoms

In contrast, bipolar depression can be debilitating. Unlike standard sadness, it often feels like a complete loss of vitality.

- Lethargy: Feeling slowed down, both physically and mentally.

- Anhedonia: A total loss of interest in activities once enjoyed.

- Cognitive Slowing: Difficulty concentrating or making even simple decisions (like what to wear).

- Suicidal Ideation: Persistent thoughts of death or self-harm.

Mixed Features Explained

Perhaps the most misunderstood state is a mixed episode. This is when a person feels the high energy of mania alongside the despair of depression. They may have racing thoughts and agitation, but feel hopeless and suicidal—a highly dangerous state that requires immediate medical attention.

Can You Have Manic Depression Without Being Bipolar?

A point of frequent confusion is whether these two terms can ever refer to different conditions. Given that “manic depression” is an outdated medical term, the answer to can you have manic depression without being bipolar is technically no. In a modern clinical setting, if you exhibit the symptoms historically described as manic depression, you will be diagnosed with a form of bipolar disorder.

However, some people experience “mood swings” that aren’t necessarily bipolar. Conditions such as Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) or severe ADHD can mimic the emotional volatility of manic depression. The key difference lies in the duration and nature of the cycles. Bipolar cycles are typically sustained for days or weeks, whereas BPD mood shifts may happen within hours. If you feel you have “manic depression,” a psychiatrist will evaluate you to see if you fit the criteria for Bipolar I, Bipolar II, or perhaps Cyclothymic disorder.

Bipolar I vs Bipolar II: Key Differences

Once we establish that manic depression is bipolar disorder, we must determine which type is present. The distinction between Bipolar 1 vs 2 is one of the most important factors in determining a treatment plan.

Bipolar I: The “Classic” Manic Depression

Bipolar I is characterized by at least one full manic episode. These episodes are often severe and may require hospitalization to ensure the person’s safety. While many ask does bipolar 1 have depression, the answer is almost always yes. Although a depressive episode isn’t strictly required for a Bipolar I diagnosis (only one manic episode is), the vast majority of people with Bipolar I experience devastating “crashes” into deep depression following their manic peaks.

Bipolar II: The Dominance of Depression

Bipolar II is often misunderstood as a “milder” version of the disorder, but this is a misconception. In Bipolar II, the “highs” are called hypomanic episodes. These are less severe than full mania and do not cause psychosis or require hospitalization. However, the depressive episodes in Bipolar II are often more frequent and longer-lasting than in Bipolar I. For many with Bipolar II, the illness feels more like chronic depression punctuated by brief bursts of high energy.

Signs and Symptoms of Bipolar Disorder

To recognize the disorder, one must look at the totality of a person’s behavior over time. The signs of bipolar disorder are often categorized into emotional, physical, and behavioral changes.

Emotional and Cognitive Signs

Beyond the high and low moods, look for:

- Inflated Self-Esteem: A feeling of invincibility during mania.

- Rapid Speech: Often called “pressured speech,” where the person speaks so quickly that it is hard to interrupt them.

- Intense Rumination: During depression, the mind loops over past failures or perceived guilt.

Bipolar Disorder Symptoms in Females

As noted earlier, bipolar disorder symptoms in females often lean toward the depressive pole. Women are also more likely to experience “atypical depression,” which includes oversleeping and weight gain rather than the typical insomnia and weight loss. Hormonal shifts—such as those during the postpartum period or menopause—can also trigger or exacerbate mood episodes in women, making the manic depression symptoms feel even more volatile.

How a Person with Bipolar Thinks

To truly understand the disorder, we must look at the internal narrative. How a person with bipolar disorder thinks is dictated by their current mood “pole.”

During a manic episode, the brain’s “reward system” is hyperactive. The person thinks in terms of infinite possibilities. They may believe they have discovered a world-changing idea or that they no longer need the “rules” of society. Logic is often replaced by impulsivity.

During a depressive episode, the thinking shifts toward “cognitive distortions.” The person may believe they are fundamentally broken, that their friends secretly dislike them, or that the future is objectively hopeless. The “bipolar mind” isn’t just moody; it is a mind where the filter through which reality is perceived has been radically altered by brain chemistry.

Bipolar Disorder and Talking to Yourself

A specific symptom that often worries caregivers is bipolar disorder, such as talking to yourself. While this can be alarming, it is often a manifestation of “racing thoughts.”

Internal Dialogue vs. Psychosis

In many cases, a person with bipolar disorder talks to themselves during a manic phase because their thoughts are moving faster than they can process them internally. Verbalizing thoughts can be an unconscious attempt to “slow down” or organize the chaos in their mind.

However, it is important to distinguish this from psychosis. In severe Bipolar I mania, a person may experience hallucinations or delusions. If the “talking to yourself” involves responding to voices that aren’t there, it is a sign of a more severe episode that requires immediate medical intervention. Most often, though, it is simply a symptom of high-level anxiety or cognitive overactivity.

What Causes Bipolar Disorder?

Understanding what causes bipolar disorder requires moving past the idea that mood swings are merely a choice or a personality flaw. Science now views this condition as a complex interplay of biology and environment.

Genetic Predispositions

Bipolar disorder is among the most heritable mental health conditions. If a parent or sibling has the disorder, your risk of developing it is significantly higher. However, it is not controlled by a single “bipolar gene”; rather, it involves multiple genetic variations that affect how the brain handles stress and regulates mood.

Brain Chemistry and Structure

Research into the bipolar brain shows physical differences in the areas responsible for executive function and emotional regulation. Specifically:

- Neurotransmitter Dysregulation: Imbalances in chemicals like dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine. During mania, dopamine levels often skyrocket, fueling the “reward-seeking” behavior.

- Brain Connectivity: The “wiring” between the prefrontal cortex (the logic center) and the amygdala (the emotion center) may be less efficient, making it harder to “brake” an escalating mood.

Environmental Triggers

While biology loads the gun, the environment often pulls the trigger. Severe stress, childhood trauma, or major life changes (like losing a job or a loved one) can spark the first episode in someone who is genetically predisposed. Even a lack of sleep can be a powerful trigger for a manic episode.

Can Mania Go Away on Its Own?

A common question for those resistant to medication is: Can mania go away on its own? The answer is complicated.

Technically, a manic episode will eventually end as the brain’s chemicals “burn out,” often leading to a sharp crash into deep depression. However, leaving mania to “run its course” is extremely dangerous. During a manic episode, the lack of judgment can lead to irreversible life consequences, such as financial ruin, legal issues, or broken relationships. Furthermore, untreated episodes tend to become more frequent and severe over time, a process known as “kindling.” Medical intervention is essential to stabilize the mood and prevent long-term brain damage.

Can You Cry During a Manic Episode?

There is a persistent myth that mania is always about “happiness.” Consequently, people often ask: Can you cry during a manic episode?

The answer is a definitive yes. Mania is defined by intensity, not necessarily joy. In many cases, mania manifests as “irritable mania,” where the person feels on edge, agitated, and hyper-sensitive. Furthermore, in a “mixed episode,” a person can feel the high energy of mania while simultaneously feeling the profound sadness of depression. During these times, a person might be talking a mile a minute while tears stream down their face—a state that is both exhausting and confusing for the individual.

Bipolar Disorder Treatments

The transition from “manic depression” to “bipolar disorder” has also changed how we treat the condition. Today, bipolar disorder treatments are multifaceted, focusing on both chemical stability and lifestyle management.

Mood Stabilizers and Medications

Medication is the cornerstone of treatment for most. Common options include:

- Lithium: The “gold standard” for preventing both mania and depression.

- Anticonvulsants: Medications like Valproate or Lamotrigine that help stabilize mood.

- Atypical Antipsychotics: Often used to bring a person down from a severe manic peak quickly.

Psychotherapy

While medication handles the biology, therapy handles the life skills. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) helps patients identify the “thinking errors” that happen during episodes. Interpersonal and Social Rhythm Therapy (IPSRT) is also highly effective, as it focuses on stabilizing daily routines—like sleep and meal times—which are crucial for keeping the bipolar brain in balance.

Lifestyle Management

Managing bipolar disorder requires a commitment to a “stability-first” lifestyle. This includes avoiding alcohol and drugs (which can trigger episodes), maintaining a strict sleep schedule, and using mood-tracking apps to catch “red flag” symptoms before they spiral into a full-blown episode.

Frequently Asked Questions

Navigating the transition from historical labels to modern medical terms can be difficult. Below are the most frequently asked questions to clarify the difference between bipolar and manic depression.

Is manic depression the same as bipolar?

Yes. In almost every clinical context, the two terms describe the same condition. “Manic depression” is simply the older, traditional name for what we now call bipolar disorder.

Is bipolar disorder the same as manic depression?

Yes. While the name has changed to be more inclusive of different subtypes (like Bipolar II and Cyclothymia), the core experience of cycling between high and low moods remains the defining characteristic of the diagnosis.

Why is bipolar no longer called manic depression?

The change was made in 1980 for three main reasons: to reduce the social stigma associated with the word “manic,” to provide a more scientifically accurate description of the “two poles” of the illness, and to distinguish it clearly from unipolar (standard) depression.

Can you have manic depression without bipolar disorder?

No. If you have the symptoms of “manic depression,” a modern doctor will diagnose you with bipolar disorder. There is no separate medical diagnosis for manic depression today.

Does bipolar 1 include depression?

Yes. While Bipolar I only requires one manic episode for a diagnosis, the vast majority of people with Bipolar I experience deep, debilitating depressive episodes as part of their cycle.

What are manic depression symptoms?

The symptoms include the “highs” (racing thoughts, decreased need for sleep, impulsivity, euphoria) and the “lows” (hopelessness, lethargy, loss of interest in life, and changes in appetite).

Can mania go away on its own?

A manic episode will eventually “burn out” and usually lead to a depressive crash, but it should never be left untreated. Untreated mania can lead to severe life consequences and potential brain changes that make future episodes more frequent.

Conclusion

Understanding that manic depression is the same as bipolar is the first step in demystifying a condition that affects millions of people worldwide. The evolution of the name from “manic depression” to bipolar disorder represents a victory for both science and the patient. It moved the conversation away from outdated “insanity” labels and toward a biological, manageable reality.

By focusing on the “poles” of the disorder, we have been able to develop more targeted treatments, from mood stabilizers like Lithium to specialized therapies like CBT and IPSRT. More importantly, the new terminology has helped peel away layers of stigma, allowing individuals to speak about their condition without the weight of the word “maniac” hanging over their heads.

If you or someone you love is experiencing the symptoms described in this guide—whether you think of them as manic bipolar disorder or the modern bipolar diagnosis—the most important action is to seek a professional evaluation. With a modern diagnosis comes modern treatment, and with modern treatment, a stable, fulfilling, and vibrant life is entirely within reach.

Authoritative References

1. National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH): Bipolar Disorder

2. Mayo Clinic: Bipolar Disorder Symptoms & Causes

3. American Psychiatric Association (APA):What Are Bipolar Disorders?

4. Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance (DBSA): Bipolar Disorder

5. Harvard Health Publishing:Bipolar Disorder (Manic Depressive Illness)

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get mental health tips, updates, and resources delivered to your inbox.